The #WellnessSoWhite debate: Is it racist?

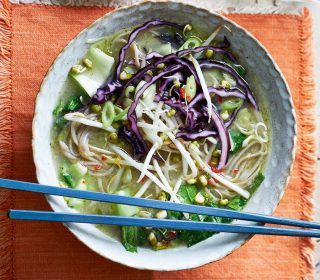

Spiralizer? Check. NutriBullet? Check. Avo toast? Check. Even if you weren’t an #eatclean devotee or didn’t go on a juice cleanse, chances are, they’ve found themselves on your kitchen worktop, Instagram or let’s face it, in your belly.

There’s no doubt that the wellness movement has shifted from a trend to arguably a national preoccupation. It’s now a $3.72trillion industry – and growing.

But while we might be encouraged to load more colour on our plates (here’s looking at you, #eattherainbow), it’s hard to overlook the irony: why aren’t more people of colour in the movement visible?

At present, there’s not one leading wellness figure that deviates from the norm: white and middle-class. If #OscarsSoWhite, there’s no doubt that #WellnessSoWhite either.

HEALTH MATTERS

Much of the criticism levelled against wellness has rarely, if ever, questioned the movement’s drastic lack of diversity. Instead, the backlash predominantly centres on how clean eating promotes disordered eating.

Leading wellness figures without credentials have also come under fire. But the absence of non-white faces deserves as much discussion and headline space.

So why is this still being met with a wall of silence? It’s concerning when Person(s) of Colour (PoC) could benefit from the movement even more.

Black and minority ethnic (BME) communities face a greater risk of heart disease and obesity, according to the British Nutrition Foundation. They’re also significantly likelier to be diagnosed with a serious mental health illness and to be over-represented in mental health institutions.

When yoga, for one, has been found to reduce anxiety and depression, why then do I still find that I’m the only brown body in the room?

LONDON’S WELLNESS MOVEMENT

There’s no doubt that the capital’s health scene can be intimidating for the average person. Be it Bikram yoga or a cold-pressed juice launch, I’ve long felt conspicuous as often the only PoC there.

London might be one of the most ethnically diverse cities in the world – 44% are now BME – so why then am I still often the only one or at least one of a few? Businesswoman Keisha Henry, 31, just about ‘got used to being the only Woman of Colour in a class’ despite practicing yoga for eight years. Does it make her uncomfortable?

‘Not really but it would be nice to see other people of colour as well.’

For others, it’s less subtle. ‘I feel alienated when teachers make comments about my hair, my body type, and other physical characteristics,’ Stacie Graham, a life coach agrees. ‘Or when other students stare at me.’

Instructors also report feeling alienated. ‘I avoided teaching in any studios for the last five years because I find [them] white-centric,’ Josetta Malcolm tells me.

So are these incidences a one-off? Or are these experiences reflective of the wellness movement in the UK at present? After all, one leading women’s health publication is yet to feature a non-Caucasian woman on its cover in 2017 (and only managed two in 2016).

The publishing world isn’t exempt either – a cursory glance at Yellow Kite Books, which specialises in health and wellness, features very few non-white authors. And of the most recognisable wellness tomes out there, none are written by PoC.

Even on Instagram, which has long championed diversity, I’m yet to see any difference. Search #yogagirl (4,083,874 posts and counting) and Caucasian women in various (and enviable) contortions fill the screen.

That’s not to say that PoC are entirely absent from the movement. It’s just that they’re yet to be given identical opportunities to hit the mainstream.

It’s challenging enough to inhabit spaces where black and brown bodies aren’t entirely accepted or welcomed. But a closer look at various healthy eateries and fitness studios across the capital reveals a more sinister reality: more often than not, communities of colour are prevented from accessing them in the first place. Classes at one central London fitness studio are £20 a pop, while supper clubs and a five-day juice cleanse can charge up to £60 and £375 a head, respectively.

When Black and Asian workers are significantly more likely than their Caucasian counterparts to be in insecure jobs or on zero hour contracts, while Muslim women are three times as likely to be out of work, according to the Women and Equalities Commission, their absence from health settings paints a bleak picture: it’s out of their reach.

REVOLUTION IN THE MAKING

It’s optimistic, however, that PoC are increasingly setting up their own spaces to combat what they perceive as their invisibility in the mainstream. OYA Retreats, the UK’s first yoga retreat for WoC, is one example. Stacie, a certified hatha yoga instructor, says: ‘Yoga has had such a profoundly positive impact on my way of living, it was important to me to create an environment where an underrepresented population of practitioners would have similar opportunities.’

In a summer that’s seen a white nationalist protest in Charlottesville end in deadly violence to most of the residents perishing in the Grenfell Tower tragedy from BME backgrounds, OYA offers a safe space for WoC to reconnect.

‘We’re all too painfully aware of the violence and hurt our communities are dealing with right now,’ Josetta, an attendee, agrees. ‘We need more healing spaces for ourselves to share, vent and celebrate.’

OYA’s since branched out into urban retreats in London, largely in part as she’s conscious that it’s not entirely financially accessible to all WoC.

While I expected OYA Retreats to be a one-off, a domino effect seems to have taken hold since last summer. More spaces accommodating PoC than ever before have launched, from yoga for Muslim women to Yogahood, a vinyasa flow yoga class that aims to tackle the practice’s inclusivity problem. It’s also regularly frequented by 20-something black males.

Yogahood has been so well-received, founder Sanchia Legister tells me, largely in part because ‘people want to see others they can identify with’.

She’s since co-founded Gyal Flex, a class that fuses hip-hop with meditation. ‘There is room for more than what’s on offer now,’ Sanchia says.

Frankly it’s frustrating it’s taken that long when PoC have increasingly built spaces for their communities Stateside. The most notable is Black Girl in Om, a leading wellness platform for WoC that’s branched out into podcasts, events and retreats. Meanwhile, Black Vegans Rock celebrates the achievements of its namesake. It’s heartening that instead of once pining for a similar revolution to hit UK shores, I’m seeing us stake our claim.

Sanchia and Stacie might have made some much-needed strides, but we don’t have to wait for others to make the change they want to see.

Each of us have the power to play a part – however small – in making health accessible to not just PoC but other minority groups too, whether it’s ensuring the venue caters to those who aren’t able-bodied, to encouraging instructors to hold classes in ethnically diverse postcodes. We all deserve to benefit from the movement, be it a single mother on a council estate to a Chelsea-based stockbroker.

And there’s never been a more pressing time either for PoC to reap the benefits of the movement. Months on from the Grenfell Tower tragedy on 14 June, at least 20 survivors and witnesses have, sadly, attempted to take their lives.

Here’s hoping that over the next few years, PoC won’t have to keep launching separate spaces and that the mainstream might just be ready to accept us.

Read more: The relationship between health and happiness