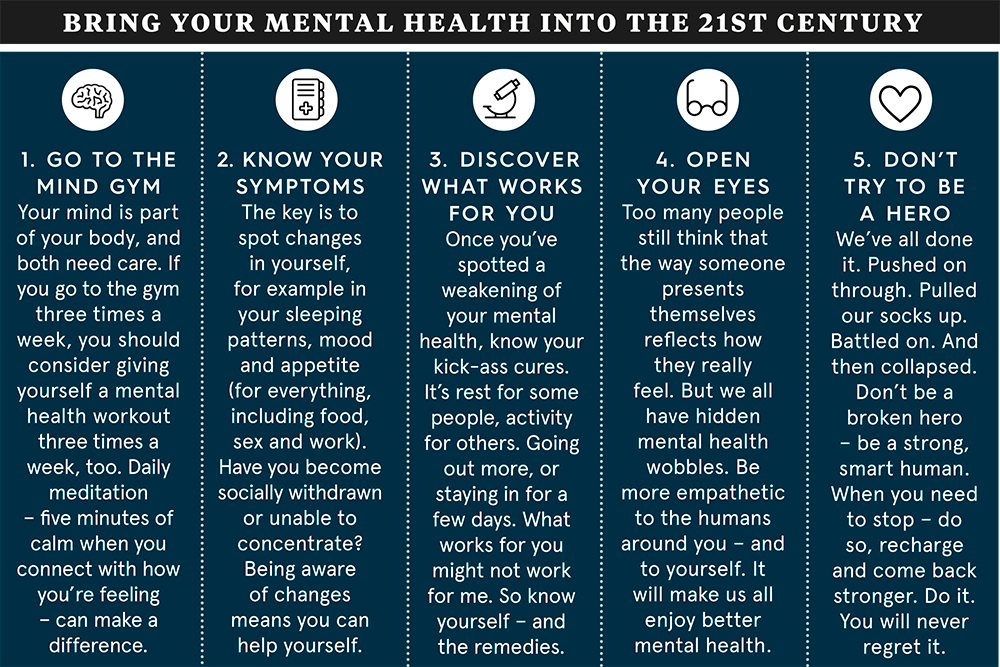

Bringing your mental health into the 21st century

THE EXPERT

Liz Fraser is an author, columnist and broadcaster. She is also the creator of the brand new kick-ass mental health platform Headcase. She has three children, a Cambridge degree in psychology, mild bipolar disorder and periods of deep depression. To cope, she runs and drinks coffee.

Unless you’ve been living off grid in a remote part of the world for the past year, you’ll have noticed one subject has been talked and written about more than almost any other – even more than the awesome and life-changing benefits of smashed avocados. It is, of course, mental health.

Mental health has never been on the pub/café/school run/flat white queue/headline agenda more than it is now. And mental health problems have never been so prevalent.

Self-harming and mixed-state anxiety and depression disorders are present in ever greater numbers in children as young as eight. Young male suicide rates have reached a horrendous all-time high, while increasing numbers of affluent professionals are experiencing nervous breakdowns in their 40s.

Student waiting lists for mental health care are so long that they often graduate before receiving any help, while suicide rates among students are almost too terrifying to comprehend. Mental health problems are the problem of our time.

Despite all the talk, mental health is still stagnating in the murky backwaters or misunderstanding, confusion, shame, fear, lack of empathy and denial. As places to hang out, these backwaters aren’t famed for their uplifting vibe.

TERRIFYING CHASM

The high-profile public campaigns, adverts and hashtags we’ve seen of late have been brilliant for raising awareness and allowing people to share their experiences, but there is still a giant and terrifying chasm between the experiences of those of us who suffer with everyday mental health problems and the way much of society treats us.

Migraines, sciatica, dandruff, cancer, even weak pelvic floor – you name it, you can talk about it and you’ll get sympathy and care. But panic disorder, borderline personality disorder, bipolar tendencies, suicidal attempts? Good luck getting those through a first date or job interview.

Many people don’t want to go down traditional routes of mental health care, for reasons including professional risk (a perfect illustration of the empathy problem right there!), not wanting it on their medical records, and not realising their problem is serious enough to need specialist treatment.

None of this is helped by the fact that we still speak about mental health in old-fashioned, musty terms and the main avenues for diagnosis and treatment have barely changed in the past 50 years.

The big problem here, in my opinion, is branding. Mental health isn’t sexy. It isn’t cool. It isn’t talked about honestly. It isn’t well understood. And it isn’t served on sourdough toast with a skinny latte. Most of all, it isn’t allowed to be funny. At all. In short, it’s not something we want anything to do with. It needs a total re-brand. The good news is that might be about to change.

UNASHAMEDLY BALLSY

New websites and apps are springing up to change the way we talk about mental health and the language we use – and to shove a firecracker up the backside of our understanding of the most common causes, symptoms and ways of accessing help.

One of these is Headcase, which I set up four months ago as a site and series of podcasts for people who want their mental health information served fresh and Instagram-friendly, with a healthy dose of humour on the side.

Unashamedly stylish, ballsy and often very funny, Headcase is just one example of a platform that’s grabbing modern technology and terminology by the mental balls and shaking it into the 21st century. And the key to this, is humour.

Writer and presenter Stephen Fry did a lovely podcast for Headcase recently, in which he said that mental health is far too important not to laugh about. Similarly, comedian David Baddiel told me: ‘When you’re laughing at something, it’s stripped naked of its power, to some extent. Comedy is often a much greater way of understanding something than taking it very seriously.’

This is exactly what mental health needs. We should be tackling it, exposing it and empowering ourselves to help our mental health, rather than succumbing to the strength of mental illness.

EVERYDAY CHAT

Until we start talking about what goes on in our heads in exactly the same way as

we talk about what’s on Netflix or the latest trainers, we will never pull it out of the dark, scary cupboard and into the light.

The more we can do this, the more we can access the millions of people who still feel they have nowhere to go that doesn’t make them frightened or feel like a failure, and the more we can help them to either help themselves or get the help they need from others. This, in turn, could not only reduce waiting lists, but also save lives.

My dream is for all businesses to be required by law to allow their employees to take up to 12 mental health days a year. No docked pay. No shame. No fear of losing a promotion. Just one day a month where we’re allowed to say: ‘You know what, I’m hitting burnout and I need to rest my mind.’ Just as they would be allowed to rest their body if they had a physical illness.

I dream that all universities will provide freshers’ packs with information in them that actually speaks to students in their language, and not that of a counsellor from 1975. I want schools to have a buddy system, where every pupil has five or 10 cards (or pokes, emojis or whatever they would use most) per term that they can use to either tell a buddy they’re not feeling OK or to ask a friend if they are OK. If everyone has them, then there’s nothing special or weird about them.

Like going to the gym with a friend, looking after our mental wellbeing should be a shared, accepted and valued part of all of our lives. We’re a long way from this.

If I say I can’t hit a deadline because I’m in a depression, the reaction is likely to be: ‘Well, can’t you just sort yourself out?’ But if I had broken my arm, there’d be sympathy. Hopefully, though, as more places to talk, write, read, listen and speak out emerge to educate and inform in new ways, society’s attitude towards the mind will finally catch up with its attitude to the body.

Read more: 3 mental health stories that prove we need to get talking