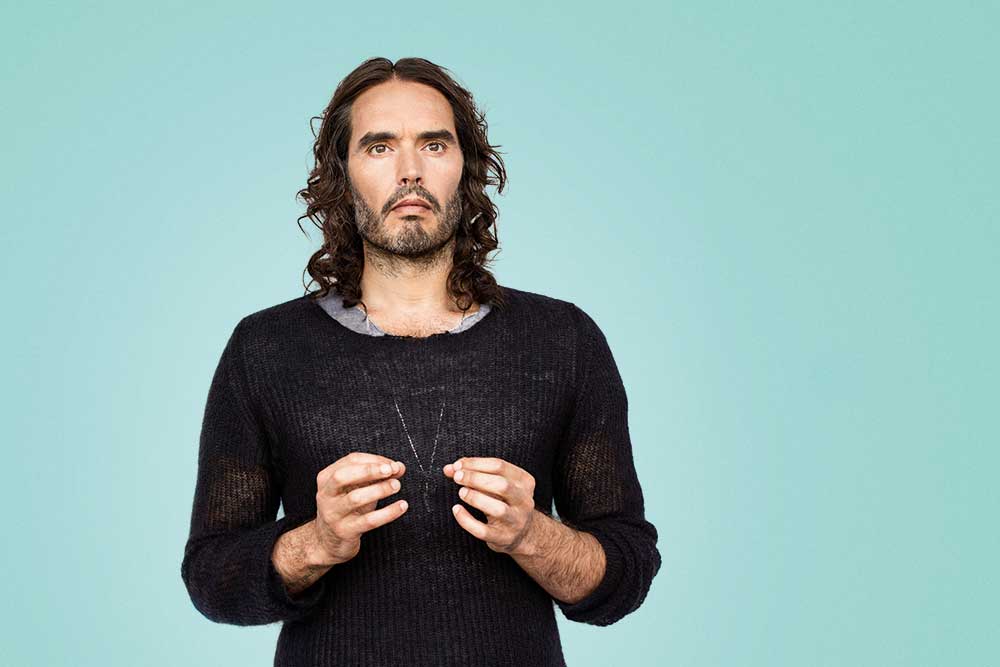

The Big Interview with Russell Brand

On a bright and breezy April evening, on the outskirts of Edinburgh, Russell Brand is confronting his past.

“The prognosis at the point I stopped taking drugs was ‘if you don’t, within six months you’ll be dead, or in prison, or in a lunatic asylum’. The way things were going, I think that was a pretty fair assessment,” he says.

“God knows where I’d have been 15 years later. Most likely dead, but certainly institutionalised and probably somewhere quite dismal and desperate.”

The grim forecast of his future was delivered by Chip Somers, a former drug addict and chief executive of Focus12 in Bury St Edmunds, where Russell checked in on 12 December 2002, realising that after years of heroin addiction, he was so beholden to drugs and alcohol and his life was so unmanageable, that something – everything – had to change.

By following the 12-step programme, a set of guiding principles for recovery, favoured by groups including Alcoholics, Narcotics and Over Eaters Anonymous, the comedian, actor and presenter achieved sobriety. Then came other compulsions, for sex, porn, food, money and fame. Over the years, Russell, now 42, stamped out each by reverting to and implementing the programme’s steps.

“I feel happier living with a person, having to pick up dog poo and change nappies than I ever did being involved in more decadent activity”

The fruits of his labour are plain to see in his domestic existence in Henley-on-Thames, Oxfordshire, with wife of nine months, Scottish lifestyle blogger Laura Gallacher, 30 – sister of Sky Sports presenter Kirsty – and their 18-month old daughter, Mabel.

“I feel happier living with a person, having to pick up dog poo and change nappies than I ever did being involved in more decadent activity,” he explains, alluding to a promiscuous past where he bedded more than 1000 women including Kate Moss, Courtney Love and Sadie Frost.

“It’s tiring picking up poo and being more ordinary and real, but it’s a relief. It feels connected and purposeful.” He’s surprised by how far he’s come and, by all accounts, it’s not over yet. “I’m curious about how I can continue to change my life using these techniques. I look at any area and think ‘am I happy with it?’. If not, am I willing to change it, do the work and ask for help? I’m a slow learner, but I’m changing all the time.”

Not content with his own transformation, Russell now wants to inspire yours. It’s why he penned Recovery: Freedom From Our Addictions – his expletive-laden re-imagination of the 12 steps. According to Russell, we all suffer from addiction, whether it’s being glued to a smartphone, bidding on eBay or munching on Haribo.

“We’ve got to examine the reasons why we do them,” says Russell. “Why are people staring at their phones the whole time? Why are people looking at porn, eating bad food, getting in bad relationships and – at the more extreme end – getting into drugs or gambling? It’s usually because of misery, sadness, discomfort, the need to escape, despair: these things can be altered.”

It took Russell 20 years to connect his addictions to childhood pain, and the most heartbreaking part of Recovery is when he reveals his abuse at the age of seven. He also describes harbouring feelings of guilt when his mum was diagnosed with cancer, and details a “tense” relationship with his former step dad. Russell kept all these woes secret until they were so engrained in his “fabric”, he never identified them as problems.

The pain was hiding in plain sight. Shortly before “graduating to porn”, he secretly gorged on packets of Penguins for comfort. He describes the ritual of un-peeling the wrappers and devouring the chocolate as “a survival tool” to cope with “the problem of being me”. By 14, he was bulimic and within a year of joining London’s prestigious Italia Conti theatre school, he’d been expelled for using marijuana, amphetamines, LSD and ecstasy. He first tried heroin in his early 20s.

“I found relationships difficult, and was looking for validation and comfort”

I’m talking to Russell in a rare moment of downtime, midway through his Re:Birth stand-up tour, a set of gigs he’d later cancel when his mum Barbara, 71, sustained numerous life-threatening injuries in a car accident, a month after completing her sixth bout of chemotherapy.

I’m keen to understand why he felt he didn’t fit in as a youngster in Grays, Essex. “I was self-conscious, unable to immerse myself in activity or regulate my emotions. I was too adrenalised,” he says. “I found relationships difficult, and was looking for validation and comfort.”

A poorly, detached mother, a non-present father (who left when he was six months old) and an only child, Russell believes an absence of “open and clear” communication denied him the chance to learn how to process his emotions. Now he’s a father, he is mindful of the importance of giving Mabel enough attention and love in the hope history will not repeat itself.

“No one wants their kid to be a drug addict. I just want to be present and available. I’m lucky my wife comes on tour with me, and I get to go off to the playground [with Mabel]. It’s me who changes her nappy when we’re out in a restaurant. I’m doing stuff all the time with her.”

“I’m going to do some films, carry on doing comedy… and showing off”

Talk of blissful domesticity is delightful, but there’s a section of the book where Russell admits he still “toys” with his old way of life, adding without the 12 steps, nothing would hold him here, not even fatherhood.

I think of Laura. Her trust in Russell’s structured existence must be absolute, or she’d spend her life fearing this might be the day his demons reclaim control. So, does he ever feel the urge to be unfaithful?

“Recovery is about having a degree of awareness, about the relationship between impulse and what impulse means. In meditation, the belief is you are not your thoughts; your thoughts are activity, so you can become an observer. It gives you a bit of time. It doesn’t mean you’re not going to have food, sex or buy stuff.”

A complex, independent and perspicacious thinker, Russell is also spiritual. Once a practising Buddhist, he now believes in a higher power and practices yoga and Transcendental meditation twice daily. The stillness is necessary to distance him from “the world, its people and opinions.” Once hooked on fame as much as any narcotic, his 2013 special Messiah Complex was so titled because, he claimed, he was “a little bit like Jesus”, with Hollywood success and a short-lived marriage to pop star Katy Perry making him a global star.

These days, he tries – and sometimes fails – to not obsesses over “external things”, like seeking approval and notoriety. In keeping with step 12 of the programme, which encourages you to look at life less selfishly, he now dedicates much of his time to helping other addicts and insists there is no longer a place in his life for self-centredness. He meets up with a therapist – his “mentor” – every couple of weeks. “It’s a big part of my life, talking about other people’s problems and my problems,” he says. Would he applaud mental health lessons in schools? Absolutely. “That’s a good idea, because there would be less shame around it.”

Before I bid Russell farewell, I ask him about #MeToo, the campaign which has drawn attention to sexual harassment. “It’s a positive movement, adjusted in an extraordinarily short amount of time,” says Russell. As part of his “amends” step, he too is repairing years of promiscuity by supporting a “litany of women’s causes”.

“It’s important in the way men and women relate to each other and reset the rules in ways beneficial to both for a long time to come. We’re in this together.”

Some might wonder where Russell Brand has gone, the bloke who resigned from Radio 2 after Sachsgate. The dangerously offensive Russell has moved on, replaced by a more balanced and contented man than he ever dreamed possible. “My priority is my little family,” says Russell, wistfully. “But I’m going to do some films, carry on doing comedy… and showing off.”

Some things never change. Thank goodness for that.

Recovery: Freedom From Our Addictions by Russell Brand is out in paperback on 17 May (£8.99, Bluebird).